Page 2 of 2

A year ago, this article started as a spewing forth of anger following news of Grambo and Dean’s last flight in Yosemite. At the time, discretion told me to set the article aside and let my emotions chill. I dug it up recently for a re-attack.

My anger aimed straight at Grambo and Dean. Their accident had been completely preventable. They were too experienced to have not known better. Having chosen to fly the most unforgiving and uber-technical line in Yosemite Valley, they accepted low light and non-ideal weather conditions. They also added a questionable variable to an already questionable gameplan. ‘Hey, let’s go ahead and make it a 2-way’... something never before attempted. We all know the outcome.

Grambo’s currency and proficiency is at an all-time high. Returning from a multi-week pillaging of the Moab desert, he carries a proud scorecard of technical wingsuit exits he’s just opened, some of which may never be repeated. Watching him fly is a pure joy. I have aspirations of learning everything I can from him, having silently promoted him to the status of ‘Mentor’. I’m not sure he knows how much I respect his style of flying.

Like all aviation mishaps, whether mechanical failure or pilot error, every accident starts with a critical link. When that link fails, all hell breaks loose. For Dean and Grambo, their particular critical link failed on exit prior to flight. It occurred in their heads, with their inability to temper ambition with reality.

They both had plenty of experience. They were both very current and very proficient. Nothing was wrong with their gear. So, what was lacking on exit? An accurate assessment of flight requirements for the given conditions, and an accurate assessment of their actual flying capabilities. Or stated a different way: Lack of judgement, and Complacency.

My good friend Chris is really tight with those guys. He’s one of the underground gang always sneaking around Yosemite with Dean, Grambo and other wolverines. I make the call to notify him. He gets a little choked up. Chris is another guy rapidly rising to mentor status in my eyes. A PhD engineer working in the laser field, a stupid strong climber training for American Ninja Warrior, father of two girls, and one of the most scientific minds to ever assess a wingsuit exit. He’s notorious for establishing solo wingsuit exits with exposed technical access in the eastern Sierras, often requiring significant free-soloing. No one has dared repeat them. With our combined academic backgrounds and penchant for details, Chris and I make a pretty good team assessing new exits. Our adventures are technical and proud.

Dean and Grambo were in the upper echelons of today’s wingsuit base pantheon. So were Kenney, Jhonny, Brian, Ludo, Dan, and many others. Experience wasn’t a causal factor for any of them. They all had it in excess. And yet they still fucked up somehow. Why?

There was a time when 1000 basejumps in a logbook was exceptional. Now it’s common for half the load to have 1000+ each. This combined ‘proof’ of our gear and methodology working phenomenally well sets us up for an insidious killer.

In professional aviation, we have 3 general categories of pilots:

- Low-time beginners

- High-time career-long professionals

- The Middle majority somewhere in between

You would expect that more experience would lead to fewer pilot fatalities, right? And yet, records show a spike in both the low and the high end of flight experience curves. Why?

Inexperience kills our new pilots.

Complacency kills our high-time pilots.

Pilots in the middle tend to do pretty well, statistically. They’ve been around long enough to develop sound skills, but not long enough to forget how quickly things can spin out of control. They’re much closer to the ‘back when I was a student’ phase of their career, so it’s easier to remember ‘I’m human, and by default, I make mistakes.’

Fast forward 10,000 hours in the cockpit (or many hundreds of WS basejumps), no mishaps, tons of experience, been there, done that, got this, nailed that… everything’s gone right for so long.

Ever so subtly, you stop preparing as diligently for emergencies. Routine critical tasks like packing, gear checks on exit, and pitching your pilot chute happen on virtual auto-pilot. You go through the physical motions, but your brain isn’t quite at the same level of active involvement. Mentally, you’re not as engaged in the details anymore. Meanwhile, life guarantees that, at some point, mistakes and emergencies do happen.

Complacency erodes our ability to catch the mistakes in time. After that, it’s a game of catch-up, with one initial mistake usually leading to cascading emergencies. Habits can be our best friend or our worst enemy. When complacency becomes a habit, you become a matter of time.

Federal Aviation Regulations are printed in books over two inches thick, and almost every regulation traces back to lessons learned the hard way (ie, fatalities). Pilot Error is the probable cause found in a large majority of aviation accident reports. This has led to the development of very successful FAA programs such as Risk Management, Crew Resource Management, Aeronautical Decision Making, Human Factors, and more… mandatory training for all professional pilots, yet completely foreign to the BASE community at large.

For so many reasons (good and bad), the cultural mindset of BASE is pretty much diametrically opposed with professional aviation. What do an airline captain and a basejumper have in common? On the surface, pretty much nothing. Airline captains are the epitome of ‘We must adhere to procedures and regulations!’ Basejumpers… well, we run from authority in every sense of the word. Yet, from a human flight perspective, basejumping (especially wingsuit basejumping) stands to learn from what the professional aviation community has been screaming for decades…‘WE ARE OUR OWN WORST ENEMIES.’

We’ll cover these ideas in greater detail in future articles. For now, I’ll wrap this up by offering a few pro-pilot sound bites that have served me well in the jumping arena, and which, in my opinion, I find lacking in most jumping circles.

- It’s all in the details. All of it. Weather, exit assessment, gear, packing, training, execution, contingencies, access, briefing, de-briefing, preparation, fitness, mindset, and more.

- Be a pilot, not a passenger. Own every aspect of your jump.

- Amateurs train until they get it right. Professionals train until they don’t get it wrong. When 100% success is required for every jump, you can’t afford to be an amateur.

- A Superior Pilot: One who uses Superior Judgment to avoid situations requiring the use of Superior Skill.

I’m tired of losing people I had always hoped to fly with. I’m tired of losing elite, world-level, tip-of-the-spear shining stars. I’m tired of adding names of close friends to my personal fatality list.

Got a call from Jeff today. Jeff never calls me. His voice says it all. It sounds like my voice when I called Chris about Dean and Grambo. It sounds like Chris’ voice when he called me about Kenney.

‘Everything alright?’ I ask hesitantly.

‘No. It’s Chris… he went in a couple of hours ago.’

Fuuuuuck! Another uber-experienced wingsuit pilot gone. Another mentor gone. Another damn good friend gone.

Experience doesn’t mean shit. It doesn’t matter how many successful jumps you have behind you. You’re only as good as your next jump. Act like it. More importantly, think like it.

I’m not the world’s best wingsuit pilot, not even close. Let’s just get that out of the way. My jump experience, skillset and numbers pale in comparison to most of those flying at the elite level around the world.

Yes, I have significantly more to learn; and yes, I’m enjoying the journey.

So, what do I bring to the table that’s so special? Built on a broad background of aviation experience, I bring a detail-oriented approach to wingsuit base (WB) that is desperately missing in our community.

What I lack in skill and proficiency, I offset with sound judgment and meticulous preparation.

I was fortunate enough to enter modern wingsuiting with a broad background of relevant expertise going back more than 20 years. An aeronautical engineering degree provided the theoretical side of aerodynamics and mechanics of number-crunching. Civilian flight school taught me the practical application and compromises of real-world aviation. Later, as a fighter pilot landing F-14 Tomcats on pitching aircraft carrier decks at night, I learned the payoffs of physical and mental preparation. I also learned the consequences of even the smallest of errors. The formalities of military funerals for my flight instructors and peers became morbidly routine, mostly from non-combat-related flight mishaps.

‘Carrier Aviation is not inherently dangerous; it’s just extremely unforgiving’

We would use this phrase to focus our priorities and mindset. Honestly, I think we were kidding ourselves. In truth, carrier aviation is both extremely dangerous and unforgiving. Unforgiving of even the most minute overlooked details in planning, of inadequate knowledge, improper training, poor execution, and most importantly, unforgiving of poor decision-making. On bad days, when shit really hit the fan and all emergency procedures were exhausted, lucky souls were saved courtesy of Martin-Baker ejection seats. Unlucky ones outside the envelope of even the best seats didn’t make it, usually as a result of pulling the ejection handle too late.

Like carrier aviation, WB requires minute attention to every detail, extensive and continual training, and precise execution of a comprehensive plan. WB exhibits all of the same dangerous and unforgiving traits of carrier aviation, if not more. Last time I checked, wingsuits don’t have afterburners and ejection seats to save your ass.

So, with most of the same flavors of associated risk, a careful observation of these two extreme communities could reasonably expect to find similarities in our approaches to risk mitigation, right?

Wrong. Nothing could be further from the truth. My observation is that the two communities are worlds apart in their approach to risk.

Carrier aviation teaches multiple backups for every procedure, meticulously briefed for every conceivable contingency (briefed because it has happened in the past, and can happen again in the future). Detailed emergency procedures (EPs) are burned into ‘brain stem power’ for reactions so fast that multi-step EPs are executed before pulse rates even flicker.

Brief the flight, and fly the brief. It’s called ‘Being a professional.’

What do I see in the WB community? Honestly, a bunch of cavalier basejumpers acting like 16-year-old kids who just found the keys to their dad’s Corvette.

Sometimes, I’ll see some basic attempts at pre-flight planning.

“Let’s do a quick morning load”

instead of

“We have to be geared up on exit no later than 10am because winds are forecast to switch up around 11”

The exit brief is usually brief (pun intended).

“I’ll exit first, you guys follow me”

instead of

“My exit direction is that house-sized boulder. Jumper 2 exits 5 degrees left of that boulder. Jumper 3 exits 5 degrees right of that boulder. Keep on your own side of me, no crossing over on this one. Now, here’s a practice count…”

More often, accident-response preparation is sadly thin.

“Is there cell signal up here?”

instead of

“In case anything unplanned happens, does everybody know I have this yellow ACR beacon in my leg wing pocket? In an emergency, response is initiated by pushing this button here…”

Overwhelmingly, I see a bunch of excited basejumpers who are stuck in old-school slick-jumper mentality. They zip into very-low-efficiency gliders, with minimal concepts of aerodynamics and energy management, and fly technical lines like they’re fueled by unlimited magic.

This amusement ride approach has become normal. Normal does not mean safe, correct or smart. Normal just means everybody is doing it, and mostly getting away with it.

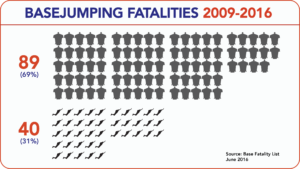

Unfortunately, the statistics speak for themselves. Of 34 personal friends lost to basejumping (not counting aviation and skydiving), 25 were flying a wingsuit. That’s 75%. For a six-year span of 2009-2016, 89 out of 129 basejumping fatalities involved wingsuits. That’s two out of every three. (For the same period, USPA reported just 6 skydiving fatalities involving wingsuits.)

Of these WB fatalities, the leading probable cause overwhelmingly points to a phrase you will be hearing repeatedly here at Topgunbase: Pilot Error.

“Pilot error is the action or decision of the pilot that, if not caught or corrected, could contribute to the occurrence of an accident or incident, including inaction or indecision.” – FAA

Translation: “They knew better. Or should have.”

For those with a critical eye, it’s obvious that changes are needed. We need changes at a fundamental level, at a core mindset level, at an educational level. If we want to grow old in this cutting edge, high risk, emergent sport, we have to adapt and learn. Fast.

If I had a nickel for every non-jumper who’s asked me ‘What’s the best way to get into wingsuiting?’… well, yeah.

Anyway, it took me a while to realize that people who ask this question are, for whatever reason, automatically on the ‘fast track’ to somewhere. Too many of my dead friends were also on this track. So these days, when I get the standard litany of excited wingsuit wannabe questions, I offer the standard ‘Find your local dropzone…’ routine. But I also make sure to add a few key points. I wish more people would learn them.

- Don’t rush… anything. Enjoy the path.

- Pay attention to the details… all of them.

- Always leave a margin.

- Never stop learning.