In 1964, NASA initiated a test program to research lifting body aerodynamics. These were stubby, ultra-short-wingspan aircraft that literally fell out of the sky.

Towed up to a release altitude of approximately twelve thousand feet over Edwards Air Force Base in Mojave, CA, highly trained test pilots perfected a high-speed flight profile with a ‘best-glide’ sink at just over three thousand feet per minute. For a glider, these numbers meant you might as well have been flying a brick. To effect a safe landing, test pilots intentionally pushed the nose even steeper from best-glide to generate surplus airspeed, building enough kinetic energy for a one-shot flare to just baaarely level their flight path prior to touchdown. Energy management and timing had to be impeccable. Real lives were on the line. With precision honed by years of high-performance test pilot training, they nailed it repeatedly.

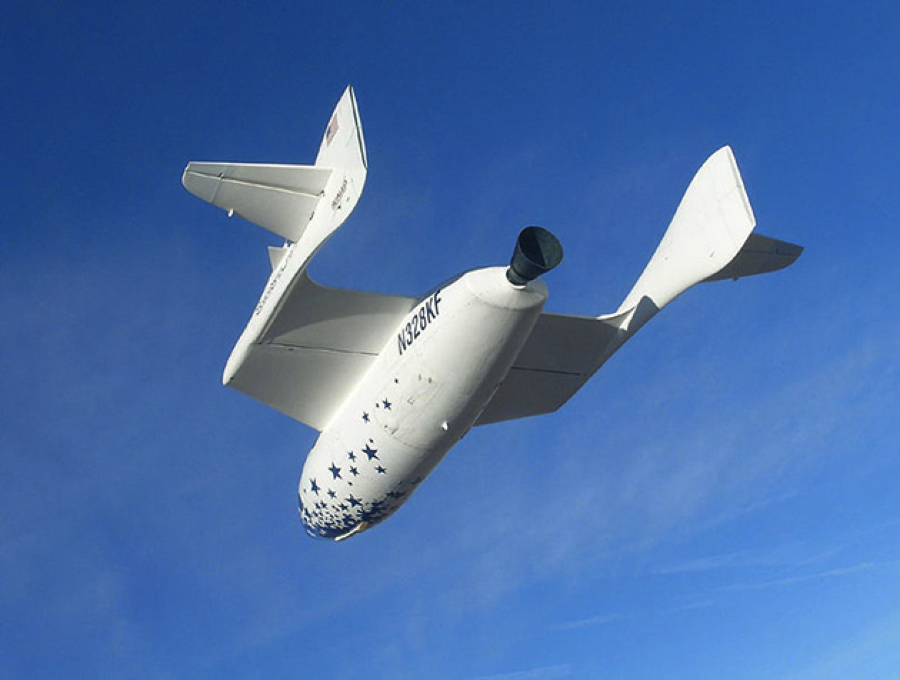

Aesthetically, the M2-F1 was just plain ugly, but its performance validated the theory of lifting body aerodynamics. The M2-F1 set the stage for development of the X-24A and other lifting body research aircraft. The knowledge gained from these incredibly high-risk programs led ultimately to the most complex flying machine ever created: the Space Shuttle. In recent years, we’ve all been witness to the cutting edge victories of Space Ship One validating private space travel. Space Ship Two is poised to offer civilian space rides for a fraction of previous costs.

X-24B over Edwards Air Force Base

X-24B over Edwards Air Force Base

M2-F1 in front of Shuttle prototype

M2-F1 in front of Shuttle prototype

All of these programs incorporate stump-winged, low efficiency, high drag lifting body platforms. That’s great, but… aren’t we supposed to be talking about wingsuits?

Well, just to keep things spicy, let’s take the above-mentioned high-risk programs, and add flexible airfoil technology. And 8 degrees of flight control articulation, meaning wrists, elbows, shoulders, neck, spine, hips, knees, and ankles. Don’t forget ram air inflation. And blended-wing-body aerodynamics. Let’s also take out the wing spar. Now combine all of these aerodynamic nightmares onto a single platform and ask a pilot to fly this crazy aircraft. Wait, let’s ask a non-pilot to fly this aircraft. Just a few meters off the deck.

We’ve just described today’s modern wingsuit community.

Today’s modern wingsuit: Nightmare for aerodynamicists and pilots, yet flown by neither.

Today’s modern wingsuit: Nightmare for aerodynamicists and pilots, yet flown by neither.

So, let’s step back from the edge for a second and assess what we’re really doing.

We’re taking an already very high-risk activity, that of jumping off a cliff and saving our butts by deploying a parachute, and intentionally increasing the risk by zipping ourselves inside a baggy nylon straightjacket.

Then we’re asking our straightjacket to inflate as fast as possible to a magical shape that enables us to scoop out of our ballistic freefall arc and sort of fly. We’ll get back to that ‘sort of fly’ comment in a bit. First, let’s look at these magic suits a little closer.

Today’s wingsuits are awesome. Seriously, modern wingsuit design teams have the coolest job description ever! They combine computational fluid dynamics and digital laser cutters with good ol’ fashioned trial and error. “Hey, let’s try this idea!” Nothing wrong with that approach. Pretty legit when you’re breaking new ground, and we’re getting some amazing wingsuits as a result. It’s honestly the 1930’s ‘Golden Age of Aviation’, except it’s the 2010‘s ‘Golden Age of Wingsuits’… a great period of flying history to be immersed in!

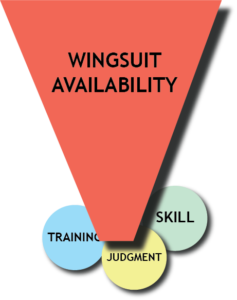

But here’s where a disconnect starts to emerge. A disconnect that leads to one of the biggest problems facing the wingsuit BASE community today: Our heritage skydiving mindset, combined with today’s explosive production and development of modern wingsuits, fools us into believing wingsuits are cutting edge, high performance flying devices.

But here’s where a disconnect starts to emerge. A disconnect that leads to one of the biggest problems facing the wingsuit BASE community today: Our heritage skydiving mindset, combined with today’s explosive production and development of modern wingsuits, fools us into believing wingsuits are cutting edge, high performance flying devices.

Well, ‘high performance’ relative to what?

From a freefall skydiver’s perspective, wingsuits are mind-blowing flying wonders available with the swipe of a red-hot credit card. Honestly, that’s about as simple and accurate as it gets.

From a pilot’s perspective, wingsuits are ultra-low-efficiency gliders with no wing spar, a tiny flight envelope, unforgiving handling qualities, high pilot workload, and no landing capability. Test pilots would legitimately describe a wingsuit as “a high-speed nylon body bag”.

The BFL would agree with this observation.

From my personal experience, I can unequivocally state that I have never flown an aircraft as unforgiving and ultra-low-performance as today’s modern wingsuit. With upwards of seventy different models of aircraft in my logbook, wingsuits are by far the deadliest aircraft I have ever flown. From helicopters, gliders, ultra-lights, gyrocopters, and airplanes. Tail wheel, single engine, twin engine, piston, turbine, and jets. Never have I focused with such intensity, flown with such commitment and precision, or exerted such physical effort as when landing an F-14 on a pitching carrier deck at night. Nothing comes close. Except when flying a wingsuit in technical or unfamiliar terrain.

Is the light bulb starting to come on?

Ok, let’s switch gears a bit. Let’s talk about the pilot inside the suit for a second.

Today’s explosive wingsuit development is grossly outpacing our poor training regiment, our lack of basic pilot skills and our lack of good judgment.

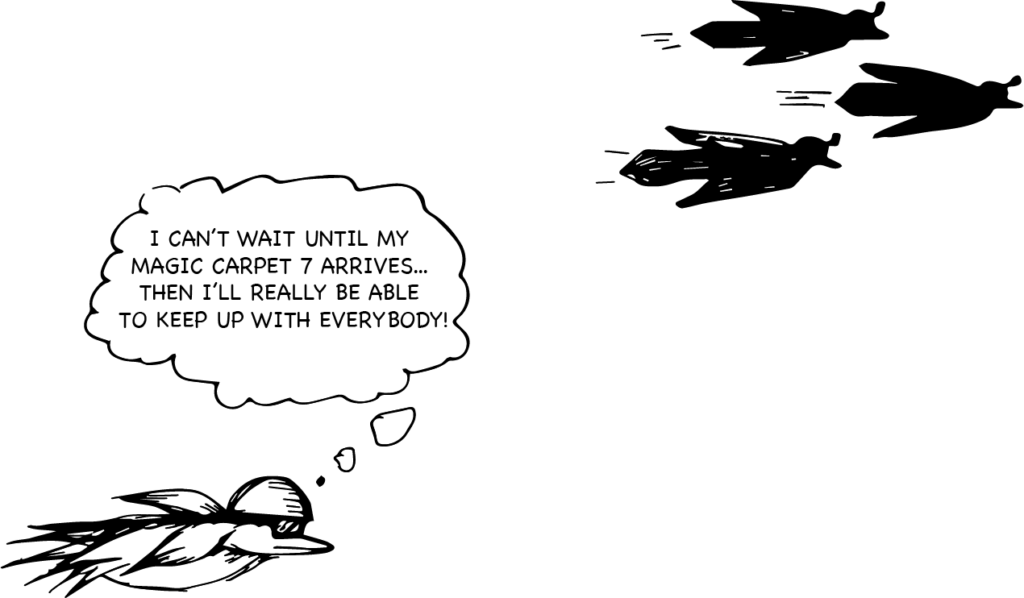

To make matters worse, most new wingsuits released today are actually easier to fly than their predecessors. No wonder when a false perception of pilot skill starts to take root. It’s an insidious circle when you really think about it.

We hear it all the time.

Here’s a nugget of aviation wisdom: A good pilot can fly any aircraft well with sufficient and recurrent training. However, just because you can afford to buy a Learjet that practically flies itself does not make you a good jet pilot. The same is true for wingsuits.

Don’t let the apparent ease of flying a particular wingsuit fool you into thinking you’re a good pilot.

Everybody thinks they’re a good driver, right? Well, take away your ABS, traction control, power steering, power brakes, rear view mirrors, the speedometer, and your gas gauge. Jump into rush hour traffic on the highway. Now we’ll see how skilled a driver you really are. Chances are, the very features making your car easy to drive mask your lack of full-spectrum driving awareness and capability.

Being a good pilot is no different. As flight instructors, we don’t take student pilots and stick them in newer, more expensive and ‘easier’ aircraft to compensate for their lack of skill. We give them focused training in basic, no-frills aircraft, and lots of it. We make them prove their competency and core piloting skills in entry-level aircraft first. Students incrementally advance to more complex aircraft… some would call this, I don’t know, slow and steady progression?

At the highest levels of commercial aviation, we find full-flight autopilots, auto-throttles and auto-land capabilities. These features make the most complex aircraft appear ‘easy to fly’ to a novice pilot. Yet, when shit hits the fan, systems malfunction, and flight plans crumble airborne, core pilot skills and judgment are the primary critical components for a safe outcome. It’s the pilot, not the airplane, who saves the day.

Sully saving the day, with zero lives lost.

Sully saving the day, with zero lives lost.

Okay, we’ve talked a little about the suits. We’ve talked a little about the pilot skill inside the suits. Now let’s get back to that ‘sort of fly’ comment at the very beginning.

“I’ve got 200 skydives, therefore I’m now qualified to fly a wingsuit.”

That statement is heard at dropzones everywhere. In most circles, this is actually considered a conservative statement! Many jumpers begin flying wingsuits with far less skydives. With visions of social media grandeur playing through their heads, it’s becoming routine to hear AFF students loudly proclaim their intentions of terrain flying in Switzerland as fast as possible. Whoa, what?

Remember the first time you really nailed a track in skydiving? Your first taste of ‘human flight’ where, all of a sudden, you found the sweet spot of perfect body position and you took off across the sky! Well, sorry to burst your bubble, but that wasn’t actual flight. It was controlled deflection of air.

“But it feeeeels like flight, and it feels good!”

I totally agree!

Later, after progressing through multiple wingsuits, “Look at skydivers falling vertically while I fly at 3:1 glide ratio. I really MUST be flying now!”

Here’s the big problem! The skydiving metric of ‘improved flight performance’ is referenced off the vertical column of air introduced to us from our very first tandem. This reference is reinforced for the recommended couple of hundred jumps before we’re arbitrarily ‘qualified’ to zip into our first wingsuit.

Here’s a dirty secret: the very same jump plane that gets you to altitude references ‘improved flight performance’ relative to the horizon. Yet, wingsuiters delude themselves by referencing the vertical air column for performance metrics. In part, because it’s what we know from our skydiving roots. In part, because we think it makes us look good as we brag about our glide distance and speeds to newbie skydivers. Wake up! We’re collectively fooling ourselves. When we truly compare wingsuits to other aircraft, we’re in a world of hurt.

Showing up at your local glider flight club for a demo instructional flight, you find yourself flying a docile entry-level sailplane with a glide ratio of 35:1 and a wingspan of fifty feet. (Fun fact: Top competition sailplanes can achieve glide ratios as high as 72:1)

The flying bug hooks you, and a sailplane pilot syllabus rapidly follows.

You sweat through ground school absorbing aerodynamics, weather, regulations, airspace, and more. That’s just the bookwork. The flight portion of your syllabus navigates you through basic flight maneuvers, takeoffs, landings, emergency procedures and the accumulation of required flight hours. Your first solo flight is the happiest day of your life! A couple of months later, after passing an intensive ground and practical examination with the FAA, your official ‘Private Pilot: Airplane-Glider’ certificate now hangs on your wall. It’s your proudest accomplishment.

Fast-forward a few hundred hours of flight experience. You’ve grown bored flying with the slow docile flight characteristics that 35:1 GR gives you. Those advanced aerodynamics books you’ve been geeking out on have given you a crazy idea. Grabbing a saw, you chop ten feet off each wingtip, leaving you with a 30-foot wingspan and a theoretical 21:1 GR. Your flights are now much faster and less forgiving. The flight controls are more responsive, your flights are much shorter, and you need to stay closer to the airport. Your wing also stalls at a much higher airspeed than it used to. Other glider pilots look at you funny, calling you “crazy” and “stupid”… “You’re gonna kill yourself, son. There’s a reason why gliders are built the way they are.”

But you’re a certified pilot who diligently trains and studies. You’ve done your homework. You enjoy being a test pilot.

The next weekend, you chop another ten feet off each wing. Now you’re down to a ten-foot wingspan (just five feet on either side of you!) with a theoretical 7:1 GR, somewhere around the glide ratio of a typical fighter jet. As expected, flights are stupid fast, really twitchy, and hard to control. You’re working hard for every second of flight. Precise energy management is of critical importance, as every knot of airspeed is precious energy that cannot be wasted. Your flight pattern is precisely planned to account for every variable of temperature, pressure, winds aloft, surface winds, cloud cover and time of day. You’ve modified Microsoft Flight Sim to simulate the flight performance of your ‘lead sled’. You diligently train to develop flight profiles that are repeatable. You build a set of known performance numbers to fly to on your cockpit instrumentation: best glide speed, target sink rate, and ideal angle of attack. All of this meticulous training and preparation enables you to glide to a stupidly fast one-shot flare at a precise point on the runway. Things happen fast and there is no time to think. Every detail must be planned, considered, briefed and executed with minimal contingency plans available. You start wearing a flight helmet. You weld a roll bar over the top of the cockpit inside the bubble canopy. You wear a parachute. You love it!

A month later, after convincing yourself that you really do have this ‘anvil glider’ flying dialed in, out comes the saw for one more downsize. A few cuts later, you’re staring at a cockpit… and not much else. Only three feet of wing, about one arm’s length, stick out from either side of your tiny little bubble cockpit. You’ve checked and re-checked the numbers. A six-foot wingspan gives you a glide ratio of 4:1… theoretically. You pick up your helmet and your parachute. This will not be a test flight. This will be controlled freefall.

So, what’s the difference between today’s average wingsuit pilot and our glider test pilot here? Both involve manned, low-efficiency, stubby-wing, and immensely high workload flying platforms. Yet wingsuits are perceived as high-performance state-of-the-art flying devices, manned by self-taught ‘freefall athletes’ with zero pilot training and no flight instruments. Our glider pilot is a highly trained certified pilot who has passed the rigorous and intense Practical Test Standards of an FAA checkride… yet could easily be perceived by peers to be a lunatic pilot with a death wish. The under-educated wingsuit community praises perceived achievement and capability; the professionally trained pilot community scorns high-risk, low-efficiency flight. Are you starting to get the picture now?

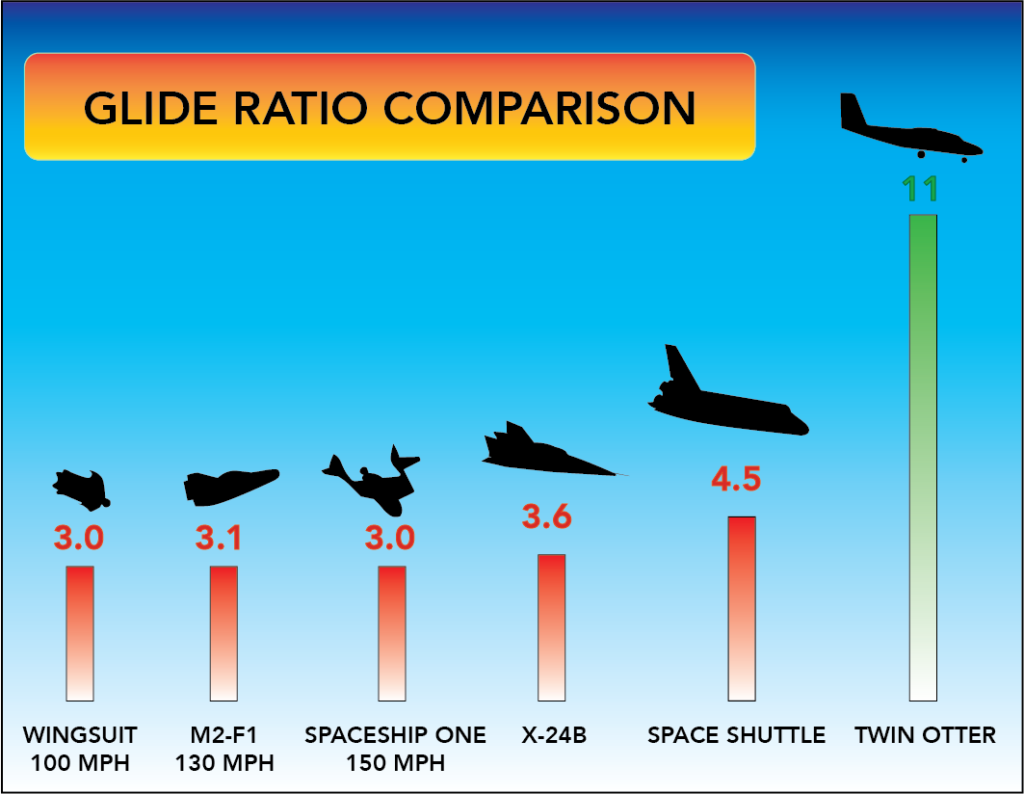

Back to our stubby-wing research aircraft at the very beginning of this story. Guess what the subsonic best-glide numbers were for them?

Eerily similar to today’s best wingsuits… yet all flown by the world’s best test pilots.

You don’t see test pilots tipping their already sketchy lifting-body aircraft off cliffs and scraping their wings down mountain terrain lines, do you? No, that would categorically be considered the dumbest idea ever, even though performance envelopes eerily match up. In wingsuits, it’s considered good sport; in a similar-performing airplane flown by an actual ice-veined military test pilot, well, that’s just plain lunacy. See the hypocrisy?

Alright, where does that leave us? Wingsuits are currently in a TBD (to-be-determined) category of aviation. We’re ‘sort of flying’, but defaulting back to our freefall modes when shit goes south or the ground gets close. On the other hand, when we are actually flying… it’s really, really sketchy flying, as in Chuck Yeager-type flight envelopes. We’re flying just enough to kill ourselves by making flying errors, not freefall errors. Pilots don’t know shit about freefall and parachutes, and wingsuiters currently don’t know shit about aviation. We need to bridge that gap. Our wingsuit community, with our deeply embedded freefall roots, believes that “we know what we’re doing, and we know how to fly.” We couldn’t be further from the truth. Our high fatality rate in wingsuit BASE proves this. Our fatalities are being caused by ambitious minds thinking they’re test pilot quality. In reality, those same minds are making novice pilot mistakes.

So perhaps on your next wingsuit flight, you could pause to reflect on just how close your wingsuit resembles a NASA research aircraft. Ask yourself “What makes ME so special to bypass any form of pilot training? Why am I qualified to fly this 3:1 aerodynamic nightmare?” If you can come up with a substantive answer, please cross-check it against the BFL.

truth! nice article !

Thanks for this. Awesome treatment of the subject; I hope it reaches jumpers far and wide.

This has been my biggest frustration coming from flying to sky diving. Excellent article.

Very well done. Thank you. And I’ll be reading more from you.

I’m a fan of the article’s intent to bridge the gap between pilots and wingsuiters, however, the article fails to realise that it’s not so black and white.

We use a parachute to land, something that we’re quite familiar with. That negates the need to have pilot-level skills for landing.

The free-fall, or flying, is done typically in danger areas that are free from other traffic. So if there’s an uncontrolled moment, it’s done in proximity of other flyers who can take evasive manoeuvres and the one out of control has a number of options to regain stability.

I can’t provide accurate stats on the WS BASE fatalities, but the risks are well understood by the vast majority of participants.

A greater understanding of your chosen discipline of flight is always beneficial, and hopefully individuals choose to expand their knowledge base as time goes on

Paul,

I’d ask you take a quick look at my article ‘Rules of Engagement’.

https://topgunbase.ws/rules-of-engagement/

The sole purpose behind Topgunbase is to stop the same circle of mistakes being repeated every season in WS BASE. It’s a niche community that is actively killing even our most current and well known members. There are essentially zero fatalities in WS Skydiving, by comparison.

Inside the WB circle of mistakes is a common theme: Pilot Error.

To accurately set the stage for addressing the Pilot Error concerns in WB, I find it necessary to first cover some broader misconceptions about wingsuits, and wingsuiting, in general.

I will assert that laziness in one’s approach to Wingsuit Skydiving grossly magnifies even small errors in Wingsuit Base. Unfortunately, errors in WB usually result in fatalities, not injuries.

Please fly smarter, and please own every aspect of your jump.

TGB

Fact is that most Wingsuit-BASE jumpers have never heard of aviation knowledge acquired in the most basic pilot training, let alone actually caring about any of it. Most just try to overcome fear before gaining some skills through repetition

Have a look here:

http://aviationknowledge.wikidot.com/sop:hazardous-attitudes

Thanks for posting this. Well written and informative. Really wish more people would read this

Great article!!! As a professional skydiver, avid wingsuiter and base jumper I see so many of my friends with low experience engage in behaviour that does not suit their skill set. There is nothing good about operating on luck. Cheers

Please see my reply above to Paul.

Inside the WB circle of fatalities is a common theme: Pilot Error.

To prevent Pilot Error, we must first regard ourselves as Pilot-In-Command of our aircraft. That ‘aircraft’ could be street clothes, a jumpsuit, tracking suit, or a wingsuit.

TGB

Extremely well-written and enlightening piece. Should be required reading before every wingsuit purchase. I applaud your attempt to put Darwin out of business.

Unfortunately, too many proximity flyers trade off common sense for maximum YouTube hits. The best info in the world won’t change that.

Amazing! thanks for the good job topgunbase. PLEASE keep us posted with more articles.

Great article for all airborn people, I don’t skydive or base jump but fly a paraglider. Our community is seeing a similar progression (??) with the advent of speed wings, with many people with far less training and experience starting out with much more unforgiving wings.

Very well written, very informative and definitely a must read for Skydivers and base jumpers. keep it up!

Really great article, Rich. This is the type of information and approach that I think will start to change people’s attitudes on how to get into, excel at, and survive wingsuit flying.

As a novice skydiver, had to suspend skydiving course due to shoulder injury, I love this article. I worked on a dropzone in the southwest for 2 yrs before my tandem and start of schooling. Sitting with other divers and listening the entire time and absorbing as much knowledge as I could. This article gives that knowledge in on place. Beautifully written and thank you.

Thanks for the article…. Very informative and analytical. I think fear it’s something that we as species can overcome through knowledge… and profound understand of physics, aeronautics and medicine, can somehow help in advancing in this and other new sports…

I can’t wait to see a wingsuit landing w/o a parachute…

Thanks again for sharing! Greeting from Chile

“Grabbing a saw, you chop ten feet off each wingtip, leaving you with a 30-foot wingspan and a theoretical 21:1 GR.”

Well, while presented in jest: aside from the description of a saw, this wingspan and glide ratio seem perfectly fine to me… but I fly hanggliders… where a 15:1 glide is considered quite nice, although wingspans in those cases are more like 33 feet.

I’m disappointed by the lack of references to hanggliders (or even the baggers… err I mean paragliders) here :p